- info@ficci.org.bd

- |

- +880248814801, +880248814802

- Contact Us

- |

- Become a Member

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Introduction

Bangladesh offers a range of tax incentives to encourage private investment in selected sectors and locations. These incentives are used to support Bangladesh's industrial policy priorities. Most take the form of corporate income tax (CIT) exemptions, providing full or partial relief to investors for up to 15 years. Reduced CIT rates are also prevalent, lowering the statutory rate temporarily or permanently to 10%-15%, compared to the 27.5% headline rate. Many incentives are available to a broad range of investors, including manufacturing machinery, computer and electronic products, the textile industry, and agriculture. Additionally, some incentives target goals related to infrastructure and social and economic development, including improving the environmental impact of investments, and skills development. However, the incentives regime faces several implementation challenges, restraining private investment.

Challenges and Inefficiencies

There are several challenges and inefficiencies in the current tax incentive framework:

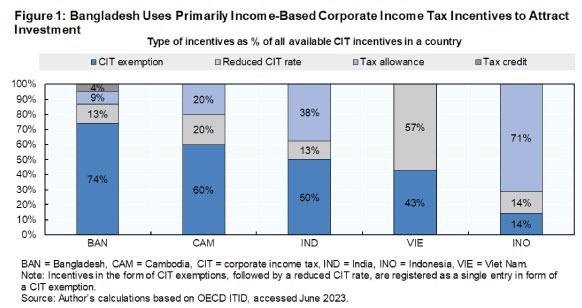

Limited Effectiveness: Bangladesh's industrial policy heavily relies on income-based tax incentives (CIT exemptions and reduced CIT rates) which often attract short-term, mobile investors and may not effectively stimulate additional investment (Figure 1). Bangladesh also provides expenditure-based incentives (such as tax allowances and credits) that are better targeted at attracting additional investment compared to income-based incentives. They align tax benefits with qualifying expenditures, promoting investments in capital assets, R&D, training, and job creation, while being more transparent and less affected by the Global Minimum Tax for large multinational enterprises. These incentives aim to reduce specific costs for investors, making investments more profitable and encouraging spending that might not occur otherwise.

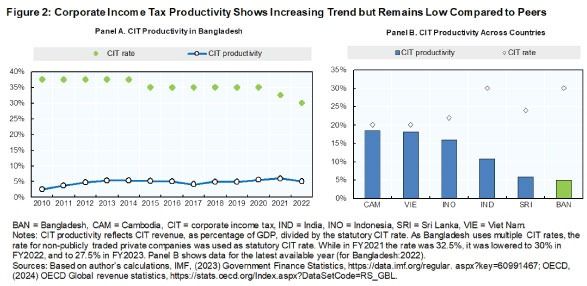

Weak Productivity: CIT productivity is relatively weak, contributing to nearly two-thirds of the country's direct tax revenues but remaining under 2% of GDP for over a decade due to a narrow corporate tax base, weak compliance, and complex tax administration (Figure 2). CIT productivity saw an increase from 2.5% in 2010 to 6.0% in 2021 before decrease to 5.0% in 2022 but lags behind peers like Cambodia. Multiple CIT rates, ranging from 20% to 45% depending on company characteristics, add to the complexity of the tax system, potentially distorting resource allocation.

Redundant Incentives: Some tax incentives may no longer be fit-for-purpose, and there is a need to reassess whether these exemptions are the preferable incentive type, particularly in view of the pressing need to construct a more integrated policy framework for investment. Reassessing and phasing out potentially redundant tax incentives could broaden the tax base and provide more fiscal space to advance with much-needed structural reforms.

Economic Distortions: Tax incentives may also create economic distortions that prevent a more efficient allocation of resources and may add to tax administration and compliance costs. Effectiveness and costs of CIT incentives are thus of utmost importance for developing countries like Bangladesh that tend to have weaker resource mobilization.

Poor Design: Bangladesh's tax-to-GDP ratio is at 7.1% (FY2024), lower than in most other developing countries, potentially limiting its fiscal capacity for reforms. While tax incentives may help to promote investment with potential positive effects on industrialization, exports, and infrastructure development, their net benefits are often not well understood. Poorly designed incentives may result in windfall gains for projects that would have taken place anyway in the absence of the incentive, wasting potential tax revenue that could have been used to expand and improve the quality of public goods like education or infrastructure.

Lack of Transparency and Evaluation: There is insufficient transparency and systematic evaluation of tax incentives, making it difficult to appraise their costs and benefits accurately. It is a positive feature to have tax incentive policy centralized at the Ministry of Finance and to consult with the relevant line ministries. It is, however, unclear how these consultations influence decision-making and to what extent the National Board of Revenue (NBR) coordinates with other bodies involved in Bangladesh's incentive policy and investment strategies.

Recommendations

Some remedial measures to the above-mentioned challenges include:

Streamline Tax Administrative Procedures: Continue efforts to streamline tax administrative procedures and facilitate tax compliance to strengthen direct tax revenues. This involves further advancing and leveraging recent initiatives, such as information campaigns and introducing an electronic tax filing system. Reducing excessive discretionary authority of tax officials and increasing the predictability of the tax environment could further support these efforts.

Evaluate and Adjust CIT Incentives: Assess whether current CIT incentives are best designed to support their stated objective. Particularly, the government should consider alternatives to current generous income-based tax exemptions available for multiple years. Targeted expenditure-based tax schemes (tax credits or allowances) might be more cost-effective for promoting investment. Bangladesh can leverage the experiences of its peers like Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, and India that have successfully implemented such measures. For this, it needs to design a well-structured policy framework that includes various forms of incentives to cater to different types of investments, simplifying the process of obtaining tax incentives to attract more investors. A scheduled reassessment of these incentives should be conducted every five years, involving key stakeholders like the NBR and relevant industry representatives.

Improve Transparency: Consolidating incentive-relevant legislation in the Income Tax Act and maintaining an investment guide with clear requirements and procedures can increase transparency, reduce policy overlaps and facilitate foreign investment. Additionally, providing English translations of incentive legislation could facilitate access to information for foreign investors.

Systematic Monitoring and Evaluation: It is needed to pursue the monitoring and evaluation of tax incentives in a more systematic and transparent manner. This includes regularly publishing tax expenditure reports with a greater degree of detail, listing each incentive measure, including estimations of tax revenues forgone, and under a clear methodology. Regularly appraising the costs and benefits of tax incentives will help in assessing if incentives have reached their policy objectives and at what cost. This evaluation should be conducted annually and involve independent audit bodies to ensure objectivity.

Broadening the Tax Base: The tax base needs to be broadened through phasing out less efficient tax incentives to provide greater fiscal space for necessary structural reforms, such as trade tariffs and facilitation reforms.

Smooth Transition Strategy: Considering the loss of preferential market access for export and as a part of the LDC graduation process, Bangladesh recently published Smooth Transition Strategy, which needs to be earnestly implemented in a time-bound manner. This would result in economic diversification through higher investment in non-ready-made garment industries.

Conclusion

While tax incentives play a significant role in promoting investment and development in Bangladesh, their design and implementation need careful assessment and continuous improvement to ensure effectiveness and alignment with broader policy goals. The proposed recommendations can help create more fiscal space, support growth-enhancing reforms, and advance sustainable development.

[The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of ADB or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent.]